I've saved the best for last. If, out of all the glorious things I saw in three weeks in Japan, I could only pick one, it would be the

I've saved the best for last. If, out of all the glorious things I saw in three weeks in Japan, I could only pick one, it would be the Tōshō-gū shrine in Nikko.

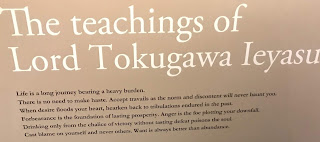

The resting place of Tokugawa Ieyasu has it all: drenched in history, dramatic landscape and a concentration of jaw-dropping art and architecture that puts it on par with any of the greatest buildings of the world. It's no wonder that this, plus Ieyasu's grandson's shrine and some other temples, form one of Japan's most noteworthy UNESCO World Heritage sites. Your biggest problem will be finding the time to see enough of it.

It started out as a more humble place. After unifying Japan, founding his dynasty of shoguns and stepping into semi-retirement, Ieyasu picked this spot in his home region for his mausoleum. The family had supported religious communities here for years. But Ieyasu was a soldier with fairly basic tastes. The place he built for himself was, legend has it, simple and elegant. This presented a problem for his grandson, Iemitsu.

By the reign of the third Tokugawa shogun, both the job and the country were stable and the Tokugawas had taken on the trappings of divine-right kings. Iemitsu wanted a funerary shrine as grand and glorious as his palaces ... and his opinion of himself. But he had a problem. Japanese respect for one's ancestors couldn't allow him to have a tomb more opulent than his grandfather's. His solution? Re-build Ieyasu's shrine with such extravagance that his own grand plans could play second fiddle.

The result is staggering.

Tōshō-gū is a complex of buildings climbing a mountain in multiple terraces. It's most notable for the deeply carved, lifelike reliefs painted in bright colours on most of the buildings. One of the gates is nicknamed the higurashi-no-mon, meaning "look at it until sundown and never tire of seeing it." You could say that of the whole extraordinary place.

The approach is up an avenue sunk between stone walls with trees towering on either side. There are other temples and attractions vying for your attention near the bottom. Don't be distracted, as you'll need most of your time for the Tōshō-gū shrine at the top. The pathway up is austere and elegant, and doesn't prepare you at all for the riot of colour you encounter when you get to the plaza at the top. To your left is a five-story pagoda with bright red eaves and balconies, green shutters, golden accents and a crazy mix of colours on the beams holding up the roofs.

There are lively carvings of animals, both real and mythological, above the windows and doors; a preview of what's to come. Across the square, next to the ticket booth, steps ascend steeply to the first of the complex's ceremonial gates. This one, amusingly, has elephants trumpeting from its corners. But not as we know them. It's rather obvious that the sculptors had never seen one of the beasts, so these seem more mythical than the dragons flying all over the buildings.

There are lively carvings of animals, both real and mythological, above the windows and doors; a preview of what's to come. Across the square, next to the ticket booth, steps ascend steeply to the first of the complex's ceremonial gates. This one, amusingly, has elephants trumpeting from its corners. But not as we know them. It's rather obvious that the sculptors had never seen one of the beasts, so these seem more mythical than the dragons flying all over the buildings.It's hard to believe that the complex of buildings through the gate is the administrative bit of the shrine, so ornate are they. There are storehouses, smaller temples, secondary gates and a stable for the horses used in ceremonial processions. All are encrusted with sculpted scenes, but the ones on the stable are the most famous. They depict monkeys demonstrating behaviours to be admired, most famously a trio representing see, hear and speak no evil. (Third panel down in the photo below.)

This area is also where you'll start to see clusters of large stone lanterns covered with moss. Each great family of the realm was invited to donate one in honour of Ieyasu; even those who had been on the other side in the civil conflicts of his early career. These reformed enemies' lanterns are placed furthest away from the main shrine building. The more faithful you were, the closer your lantern was to the great man's remains, and the larger and more opulent it was likely to be.

Walking through this "L"-shaped administrative level takes you to another set up steps, atop which you'll find an esplanade with two bell-towers, a temple building to one side and a selection of more impressive lanterns. The most interesting is a European-style oddity, cast in bronze and decorated with barley-twist columns and shields. There's some debate over whether this gift from the Dutch East India Company was crafted by clueless artists who didn't realise they incised a flipped Tokugawa crest, or whether the whole thing was installed by clueless Japanese workers who didn't know what European lanterns looked like. The local guides relate the first story. A hard look validates the second. The whole thing is clearly upside down.

The temple to the far left seems an afterthought amidst everything else here, but it's worth going inside to see the magnificent, writhing dragon painted on the ceiling and to have the priest demonstrate how the building's acoustics were designed so that any sound made directly under the mouth of the creature is amplified.

The most beautiful thing along this esplanade, however, is the gateway to the inner sanctum ... this is the higurashi-no-mon ... and the walls spreading out from it that enclose the buildings at the next level. The gate has multiple levels of dragon heads jutting outwards, with lashings of gold leaf,

white plaster guardian dogs and dragons who stand out by their lack of colour,

and scenes of particularly jolly Japanese people going about their lives.

Each panel of the surrounding carved cloister has three levels of carved decoration representing heaven, earth and water. This gave sculptors a broad scope which they lovingly filled with a dazzling collection of waterfowl, peacocks, clouds and flowers. Any one would be a masterpiece worthy of long concentration in a museum. The fact that there are 25, and these aren't even considered one of the major sights within the complex, gives you an idea of just how much there is to see here.

Climb up and through the gate, which is formally known as the Yōmeimon, and you'll come to a large courtyard in front of the main temple building, which lies through yet another ornate gate. This one has particularly magnificent statues of guardian dogs and dragons standing on the roof corners.

As a mere mortal you don't get to go through that one, however, but have to go around to the side, get rid of your shoes and join a shuffling queue of tourists. There's no photography allowed in the main shrine building, but it doesn't really matter; it's yet more of the exquisite high-relief interplay of flora and fauna with more crazy colours and abundant gold leaf.

Priests bustle quietly down the red-lacquer walkways on the inside of the cloister, which surrounds several other, smaller ceremonial buildings as well as the main one.

One, for example, is a performance stage for ceremonial dances. Another area holds a line of brightly-painted sake barrels ready for holy offering. A door nearby exits into the woods, giving access to Ieyasu's grave.

Above the door is one of the most famous carvings in the whole place, a peacefully sleeping cat. It is lovely, though I'm not quite sure why it's gained such fame as there's far more impressive work here. Nor is it representative of what's through the door. That would have been better shown by a horse, collapsed with exhaustion after being pushed to its limits ... because that may well be how you'll feel after your pilgrimage to the pinnacle of Nikko Tōshō-gū.

I didn't count the steps, but I'd guess the climb is the equivalent of scaling a 15- or 20-story building. The way is all paved with smooth, even stones and grand staircases, and you can stop at landings to admire the gorgeous forest of Japanese cypress you're climbing through, but it's still quite an effort. Thankfully, there's a water fountain and benches at the top, before you encounter the holy of holies.

At this summit, the colour falls away and the pallet is mostly black, whether that's the paint on buildings or the patina of bronze. Even the tree trunks and the shadows between them seem thicker here, lending to the sombre atmosphere. There's another, short flight of stairs up to a small temple, then a path around it and one last burst of steps up to a walled, rectangular courtyard cut into the gentle slope of the mountainside. Closed bronze gates bracketed by snarling bronze guardian dogs block a straight-line access to Ieyasu.

You'll walk around the side. His remains lie in a bell-shaped bronze container capped with a pagoda-style roof, sitting atop a series of stepped octagonal platforms that rise like a pyramid to lift him to heaven. While there's a steady flow of people, it's nothing compared to the crowds below and everyone is respectful of this solemn place. His people proclaimed Ieyasu a Shinto deity after his death and there's no denying that this place of extreme beauty, surrounded by swaying cypress in the quiet mountain air, touches the divine.

If you want to know more about Ieyasu the man, once you trek back down from Nikko Tōshō-gū your ticket also gets you into the museum where you'll find many of his personal effects, a manga film about him and the treasures of the shrine. There's also a small cafe here where you can get drinks, sandwiches and cakes.

If you want to take in all the details and climb to the summit, then digesting the wonders of Ieyasu's mortuary complex will take you at least four hours. If you're coming from Tokyo you will have spent two hours getting here and will need the same to get back, so that's most of your day. Yet Nikko Tōshō-gū is only part of the UNESCO World Heritage site. The temple you passed at the bottom of the processional entry, Rinnō-ji, the Futarasan Shrine and the mausoleum of Ieyasu's grandson, called the Taiyuin, sell tickets for a combined entry. Unless you have two days here, or are a remarkably quick sightseer, don't make the mistake of buying this ticket first ... as we did ... because you'll never have time to see everything. We had a good wander around Rinnō-ji, and it is as impressive as some of the great temples of Kyoto, but didn't have time for anything else.

In fact, if we'd had the flexibility in our agenda I would have loved to have stayed several nights in Nikko. You'd really need to see the temples over two days, not just to have enough time but to give your brain a bit of a break from all that whirling colour and dense detail. But there's much more here. The town itself has an almost Alpine feel, with lots of high-peaked wooden buildings nestled against the mountains. We passed loads of intriguing shops and restaurants. In a land that doesn't do much dairy, local specialities included cheese and baked cheesecake. There are hot springs, hiking trails, a mountain lake and a historical amusement park populated with costumed performers from the golden age of the Shogunate.

All this makes Nikko not only the place with the most magnificent tourist attraction I saw in all of Japan, but the place I most want to return to. One taste wasn't nearly enough.