Sometimes, the most spectacular sights are not the “must sees” trumpeted in the guidebooks. The Carthusian Monastery, or Charterhouse, of our Lady of Miraflores is a case in point. It merits only a small aside in descriptions of nearby Burgos, was almost empty of other visitors while we were there and I can’t remember ever seeing it mentioned in art history or architectural surveys of Spain. Yet its royal tombs, vivid altar and fascinating choir screen make it one of the most achingly beautiful places I’ve ever visited in Spain. Its emotional impact is heightened by the silence of the site and the feeling that you’re uncovering the undiscovered.

It is similar to, but in my opinion much better than, the burial chamber of the Catholic Monarchs in Granada, which you’ll wait in a queue to get into, pay for, and explore shoulder to shoulder with other tourists, watched closely by guides who won’t let you take photos. There’s a reason for the artistic similarity. The tombs at Miraflores celebrate the parents and brother of the great Queen Isabella, who lies in that monument in Grenada and who closely oversaw the design and construction at Burgos. But while the magnificence of Isabella’s burial place is a bit over the top, and the altar features far too many scenes of gruesome martyrdom for me to love it, her parents rest in a stillness and gentleness that offers heaven without quite so much suffering.

I stumbled on Miraflores’ miraculous little piece of heaven while searching for a place to break our journey between Salamanca and Vitoria. It’s only a three and a half hour drive, so a stop wasn’t strictly necessary. But it seemed a shame to be driving through the heart of the ancient kingdom of Castile and León without stopping to see any of its treasures. It was also my day to set the agenda between two full days of battlefield tourism (read about that here), so I was looking for some balancing art history. Valladolid, Palencia and Burgos were all highly-praised spots along the route, but they were also bustling towns. I was looking for something quieter. And, after our perilous adventures in the world’s most constricted multi-story garage in Salamanca, someplace that offered stress-free parking. A little monastery on the outskirts of a town fit the brief.

Miraflores is still a working monastery of the Carthusians, and as such is known as a Cartuja in Spanish or Charterhouse in English. (The English school of that name was founded in a repurposed Carthusian monastery.) Charterhouses are always a good bet for serenity. Members of the order are essentially communal hermits, spending most of their day in isolated prayer in and having little to do with the general public, coming together only to eat and group services.

Their distinctive, hooded, pure-white robes give them a ghost-like character, if you’re ever lucky enough to see one. The fathers here stay on their side of the enclosure. Two lay employees were on hand to keep an eye on things, work an admissions desk and oversee the small shop next to it. The monks are present, however, in the guidebook you’re given on entry. “As it’s not possible for us to accompany you personally, we have put a special interest in preparing this booklet for you,” they write. There’s a personal touch across the copy as the author speaks as “we” and gives you insight into their home and the features about which they are most proud. And the things you can buy reproductions of in the gift shop. A life of quiet contemplation still needs funding.

Visitors approach up a wooded road that emerges into a clearing with a cross in a grassy circle and the church complex behind it, all behind a pale stone wall. Everything is pristine and tidy, “on brand” for the men in their spotless robes. You cross through a large gatehouse before coming into a cloister which, unusually, sits in front of the church. Entry is free but donations are encouraged. Or you can splash out on products produced by the monks. In line with their charterhouse’s floral name, they’ve created a scent that wafts through the church. You can buy candles impregnated with it, or bottles of scented oil, amongst other items produced by the order. That includes bottles of Chartreuse, the distinctive green liqueur made by a more famous French branch of Carthusians.

There are seats in the cloister courtyard, and Gregorian chant piped gently through a sound system, to give you a chance to contemplate the decorative details of the church front. There are royal crests, a pieta and lots of carved foliage writhing over gothic points and pinnacles, but the majority of the surfaces are plain, white stone. You enter through a sober entry porch and atrium, both so austere you could almost start to wonder if you’re really in Spain. A portrait of St. Bruno, founder of the order, with the ghostly white skin, elongated form, and dark and brooding mood so typical of Spanish art is there to reassure you. We paused briefly to say our apologies for making such a spoiled dog his namesake. Then it was on to the main event.

The body of the church itself starts with the vestibule of the faithful, the only part where the un-ordained would have been allowed to go in the past. This isn’t a bad spot. There are lovely stained glass windows above you and some nice art on the walls, but the dominant feature is the wrought iron screen that separates you from the rest of the church. Through it you can clearly make out … but not get close to … all the magnificent art. If you liked nice things, it was a clear incentive to take holy orders and cross to the other side of the fence.Moving on to the lay brothers’ choir, the decorative detail instantly ratchets up several levels. There are delicately carved wooden choir stalls writhing with lush leaves and flowers. Two altars form the bulk of a dividing screen from the next part of the church, each centred on a triptych of beautiful paintings and clothed in gold leaf. The screen, with its pedimented doorway between the altars, is topped by wooden figures of the Virgin Mary and dancing angels. The original paintwork is still bright, showing off jolly patterns and the merry swing of their dress fabric. Despite the solemn atmosphere, the decorative scheme conspires to make this a happy place.

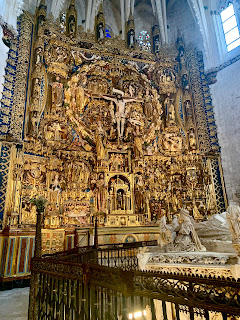

Those dancing angles are welcoming you into the holy of holies, the fathers’ choir. Here are more wooden stalls, equally lavish in their carving, but you don’t notice. Because the main altar looms above you, a wonder of three-dimensional carved, painted, and gilded scenes surrounding a crucifix encircled by a line of angels. And in front of that, the extraordinary tombs of Juan II and Isabel of Portugal. Carved in alabaster, the two are so lifelike you’d swear they got up for a ramble around the church when your back is turned. They lie on a high plinth that’s essentially a miniature gothic building, figures carved in lavish detail sitting in alcoves reminiscent of the nearby choir stalls.

If that’s not enough visual stimulation, Prince Alfonso rests to one side in an equally gorgeous masterpiece of carved alabaster, though instead of sleeping he’s shown on his knees in perpetual prayer to the high altar.

You could spend hours here reading the tombs and the altarpiece like a comic book. Each polychromed scene or carved figure has a story to tell. Each small part is a masterpiece of craftsmanship, although the altarpiece is so busy and so heavy on the gilt that you can lose focus if you look at the whole thing rather than concentrating on individual bits.

I was entranced long after my husband had drifted on, gamely content to read a book out in the cloister while I continued in my sculptural raptures. Later he asked me why I loved Miraflores so much when I’d had such a negative reaction the day before to the overzealous decoration in the New Cathedral of Salamanca. I think it’s because the decorative abundance in Miraflores exists in a quieter space. The church building itself is almost austere. And the tombs, extravagant as their carvings might be, are pure white, thus stripping out a layer of distraction.

I would have been content if that was all there was to see, but you also get to check out a sacristy packed with reliquaries and three side chapels turned into museum spaces. The largest offers more history about the charterhouse and offers up some recently-restored artworks for closer inspection. Another is a spectacularly-frescoed room from the baroque period that’s recently been restored. The third serves as a treasury, showing off some of the church’s finest accessories, and tells the story of some of the artwork lost to Miraflores in harder times. Including one piece knocked off the tomb and sold to the Met’s Cloisters museum in New York. (A modern copy seamlessly sits within the tomb now.) While the complex feels like the most peaceful and prosperous place in the world, and everything seems in perfect condition, the Cartuja went through difficult times along with Spain, surviving war, pillage and threats to religious orders. Its current form sends a message of optimism: have faith, and all will be well.If you plan to visit, do check the hours on the website as they typically close for lunch from 3-4. There are also no tourist services up here beyond a toilet. The fathers may be happy to sell you a rosary or scented oil, but encouraging people to stay for food and drink would break the contemplative atmosphere of this special place.

No comments:

Post a Comment