However ... there are three exceptions to that rule in the town centre. These attractions are so popular that you really should organise your approach, pre-booking tickets where you can and building your itinerary around them.

The first, and the one almost guaranteed to sell out if you don’t book at least two weeks before you arrive in Naples, is the Sansevero Chapel. To be honest, I was sceptical. This wasn’t in my art history textbook. I’d never heard of the artists involved. I can’t remember anyone even mentioning it when I visited the city 20 years ago. Now, thanks to social media ratings, this Rococo chapel with its statue of The Veiled Christ seems to top every Naples visitor’s bucket list.

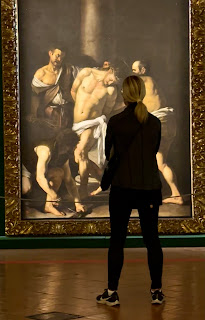

Every so often, the vox populi is right. Sansevero is a blockbuster well worth the advance booking and the queuing; both necessary because it’s quite a small place. Yes, Giuseppe Sanmartino’s life-sized sculpture of the dead Christ under a diaphanous shroud is a virtuoso act of marble carving that deserves its acclaim. Most visitors circle it multiple times to drink in its glory. I hadn’t realised, however, it’s just one of a whole sculptural cycle. Several of these are equally flamboyant, showing off different sculptors’ abilities to capture flesh beneath thin draperies or the human body entwined in a fishing net. This is a mortuary temple, and most of these figures are monuments to the Princes of Sansevero and their nearest and dearest.

Most of what you see here dates to the mid-1700s and represents a zenith of Italian Rococo. There are 28 different sculptures packed into the room, set against a background of multi-coloured marbles, multi-layered moulding and a multi-arched roof. I don’t think there’s an unembellished square meter in the whole place. If your eyes get bored, you can put your brain to work puzzling out the Masonic messages that the commissioning Prince had integrated into the decor. It’s a shame the 18th century music being piped into the place wasn’t The Magic Flute, just to drive home the mystical Masonic vibes.

You’ll be on sensory overload as you leave through a side door … but the Sanseveros aren’t finished playing with you. As was the fashion of the day, the Prince also dabbled in both science and alchemy, and in the crypt you’re greeted by two gruesome but fascinating life-sized skeletons covered with a perfect representation of veins and arteries. The Prince had such a reputation as a wizard that for centuries it was rumoured they were real bodies, and that he’d made his subjects drink some fiendish potion that hardened and preserved their circulatory systems. Modern testing shows the figures are real skeletons enhanced with wire, wax and silk, but the knowledge doesn’t make them any less frightening. Kids will think this is the best thing in Naples. (After the pizza.)

I’m not kidding about booking in advance. I didn’t even see signs of on-site ticket sales. Be ready for entry with your pre-paid QR code (tickets are €10), or you’re not getting in.

The cloisters of Santa Chiara are another religious site in the historic centre, but they will conjure entirely different emotions. Where the Sansevero chapel is bombast, sensual assault and magnificence, this enclosed garden … still used by the same order of nuns who built it … is a rare patch of peace and quiet in this frenetic city. It’s worth the €7 entry fee just for the soothing pause in your day. You don’t have to pre-book, but you will need to queue. It’s so big inside, however, that the crowd you waited with melts away. I suspect many people pop in, take the requisite photos and leave, but there are ample places to sit and simply enjoy the atmosphere. The best spot, on a sunny day, is a little pavilion with fountains and benches in it about a third of the way around from where you enter.

Santa Chiara draws the crowds because of its extraordinary majolica tiles. (Top photo) Fanciful scenes and writhing vegetation in blues, yellows and greens cover arcades of octagonal columns and the benches between them. These form two avenues that cut across the square garden with a broad, octagonal meeting point at the centre. Few of the scenes on the tiles are particularly religious. There are hunting parties, trading ships putting into harbour, and mythological processions. When we do get a nun popping up, she’s feeding cats. The first mad cat lady in art?

The tiles were painted and installed at about the same time the Sanseveros were building their chapel, but the overall effect is very different. This is possibly because there are big squares of serene garden to break up the decorations. Or perhaps because the covered walkway around the outside of the square is frescoed with older, gentle religious scenes, now much faded. There’s a particularly wonderful depiction of Saint Francis shaking a large hound’s paw that is my favourite depiction of the patron of animals anywhere. Off to one side of the cloister you can also pop in to see the nuns’ presepe, or nativity scene, which has to be one of the most magnificent in Naples. (I’ll return to this in an upcoming article on presepe.)

The third site, perhaps only worth putting on your agenda if you’re an opera fan, is the Teatro San Carlo. This is the oldest continuously operating opera house in the world and, as such, was the template for pretty much every opera venue that followed until the late 20th century. Getting tickets to see a production will take coordination and at least €65 for a decent seat (overall, prices are cheaper than in London), but you can take a short tour of the building for €9. Unfortunately tickets are not bookable online, and the ticket office is not very helpful with information in advance even when you contact them directly. Tours are liable to be cancelled if there are rehearsals, and the schedule for that seems … extremely flexible. So the best way to secure tickets is to turn up at the box office the morning you want to go, and try to get tickets for one of the two English language tours. Fortunately, the historic centre is a compact area so you’ll have plenty to do while waiting for your appointment.

The tour starts at the main public entrance just across from the enormous Galleria shopping mall. The foyer and grand staircase are almost plain, grey-white marble spaces, curiously short of ornament in this city of excess. The hallways surrounding the entrances to the boxes are almost sepulchral in their cold austerity. Other cities took the basic architectural model and added to it; this is practically streamlined Danish design in comparison to Paris’ Opera Garnier.

The Neapolitans have saved their decorative attention for the performance space. Here is the classic horseshoe-shaped auditorium, with five tiers of boxes towering over a main floor that’s much less raked than more modern theatres. Apollo, god of music, swirls heavenward in his chariot on the ceiling above, sending light and opera down to us mere mortals. Details on intricately-worked white plaster walls are picked out in gold leaf. All of the upholstery was originally royal blue, to honour the Bourbon rulers who built the place and lived in the attached palace, but a renovation in 1844 brought in the deep red velvet which most of the world’s opera houses have since copied.

While the stage, its curtain and the large orchestra pit (an innovation suggested here by Verdi) are impressive, it’s hard not to turn your attention to the royal box. It’s clearly the star of any show. Its framing draperies and enormous crown jut upwards through almost two full tiers above it. The king and court had direct access to their level from the palace, eliminating the need to interact with the public. But the king made sure that he could see everyone by prohibiting curtains in the boxes. And everyone could see him because there’s a mirror in every single non-royal box reflecting the people beneath that decorative crown. The audience watched the reflection for their cues to applaud or remain silent. Just follow the king’s lead.

The tour ends in a large event hall that was rebuilt after WWII damage. It’s a functional space with lovely French windows leading out into a garden with views to Castel Nuovo and the sea. You can’t linger here, but when you return to the main stair where you entered you can turn left and go under the stair rather than right to the exit. You’ll then find yourself in a gorgeous cafe that’s directly under the seats in the stalls. It’s an elegant place with a good range of cocktails at prices that aren’t any higher than other venues. (Again, much cheaper than Covent Garden in London.) We happily settled in here for a while. You can actually get in without going on the tour; a side door leads out to the square in front of the palace, just across from the Piazza del Plebiscito.

You can easily do all three of these sites in the same day. Pre-book your Sansevero Chapel entry for 1 or 2, any day but Sunday. Start your day at the Teatro San Carlo box office when it opens at 9. See if you can get tickets for one of the English tours, usually at 11:30 or 15:30. If you snag the morning tour, have a stroll around the Piazza del Plebiscito and linger over a coffee at a pastry at Gambrinus, Naples' most beautiful cafe. You can then go to the cloisters, which are in between the opera and the chapel, in the afternoon. Or swap that around if you're on the afternoon opera tour. There are countless places to eat and drink along the route to offer sustenance in your day of opulent sightseeing.

The tour ends in a large event hall that was rebuilt after WWII damage. It’s a functional space with lovely French windows leading out into a garden with views to Castel Nuovo and the sea. You can’t linger here, but when you return to the main stair where you entered you can turn left and go under the stair rather than right to the exit. You’ll then find yourself in a gorgeous cafe that’s directly under the seats in the stalls. It’s an elegant place with a good range of cocktails at prices that aren’t any higher than other venues. (Again, much cheaper than Covent Garden in London.) We happily settled in here for a while. You can actually get in without going on the tour; a side door leads out to the square in front of the palace, just across from the Piazza del Plebiscito.

You can easily do all three of these sites in the same day. Pre-book your Sansevero Chapel entry for 1 or 2, any day but Sunday. Start your day at the Teatro San Carlo box office when it opens at 9. See if you can get tickets for one of the English tours, usually at 11:30 or 15:30. If you snag the morning tour, have a stroll around the Piazza del Plebiscito and linger over a coffee at a pastry at Gambrinus, Naples' most beautiful cafe. You can then go to the cloisters, which are in between the opera and the chapel, in the afternoon. Or swap that around if you're on the afternoon opera tour. There are countless places to eat and drink along the route to offer sustenance in your day of opulent sightseeing.