It is nearly impossible to explain the impact of the original Star Wars film to fans who weren't there from the beginning. Which, when it comes to the thousands flocking to see the end of the saga on its opening weekend, now means most of them.

It is nearly impossible to explain the impact of the original Star Wars film to fans who weren't there from the beginning. Which, when it comes to the thousands flocking to see the end of the saga on its opening weekend, now means most of them.I can still remember the details of that hot, humid summer night in July of 1977. The film had been out in St. Louis for about a month; a buzz had been building but it was far from epic. I'd wanted to see it earlier, but we'd gone on holiday to see family in LA right after school had broken up and I couldn't convince anyone to see it with me. So I'd been writhing in anticipation for a fortnight and must have been one of the few people in the universe who had read the book before seeing the film. Yes, some enterprising marketer had released a paperback version of the story into airports when the film launched.

My friends and I had talked our parents into driving us across town to one of the few cinemas that retained its original, full-size screen. In the late '70s the economy was bad, the film industry was in crisis and owners of grand old theatres were chopping their big auditoria and broad screens into an array of smaller screening rooms. The birth of the modern cineplex. But not, in 1977, at Creve Coeur cinema.

It's also worth remembering that at the time science fiction was out of fashion, and the TV shows where it made its only stand (reruns of Lost in Space or British import Space: 1999) had fairly dreadful special effects. Grand, orchestral film soundtracks had also been left behind in the '60s. Or at least they were certainly beyond the experience of the average 12-year-old. So when the lights went down and those mesmerising letters started receding in a way we'd never seen before to the fanfare of a grand overture, we were amazed. Then the first imperial cruiser slid into view ... and went on and on across that giant screen ... and we had to remind ourselves to breathe. We had never, quite literally, seen anything like that. And the same could be said for everything that followed in the next joyous two hours.

The first video recorder and player wouldn't be released in the USA for another two months, and it would be years before watching movies on demand at home became a part of our lives. We were used to films coming and going. They might reappear on television a few years later, or maybe get a cinema re-release every few years (which is how my generation saw all the Disney classics), but if you really loved a movie you needed to see it again and again before it disappeared. Which is why I saw the original Star Wars 10 more times before it left cinema screens. There was no hope of buying a copy of the film for years, but Topps issued photo cards with their bubble gum. I had every one, assembled in order in a sort of DIY comic book version of the film.

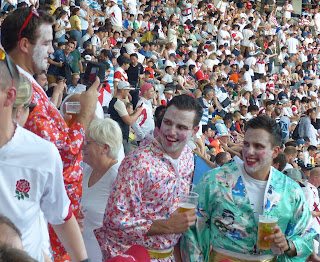

None of the films that followed had quite the same emotional impact. My fandom never grew to Comic Con or cosplay dimensions, though I did attend a friend's '70s themed hen party as Princess Leia because it's the only costume I could come up with from the whole decade that wasn't a fashion embarrassment. But the franchise probably represents one of the longest-running relationships in my life. Forty-two years is a long time to be emotionally involved in a place and a group of people.

So there was a lot riding on Episode 9, promised as the conclusion of George Lucas' epic vision of three linked trilogies telling a multi-generational story of ambition, love, fear and redemption. Director JJ Abrams has delivered everything that the 12-year-old me would have wanted. Critics have been more lukewarm but may be missing the point. Fans like me aren't judging this on its artistic merits, we're looking for closure. We want someone to wrap us up in a comforting blanket of fond childhood memories, give us a cup of cocoa and assure us that everything comes right in the end. 12-year-old me is very, very happy.

Every major plot line you want to be wrapped up is done so in a plot that zips along at a roaring pace and stretches credulity far less than some of the other films. There are no boring bits nor superfluous adventures to give minor characters plot lines. Kudos to the scriptwriters who started with excess Carrie Fisher footage and managed to build a believable ... indeed, critical ... role for her character without using CGI. Of course, it's not just Leia. Pretty much everyone who's ever mattered shows up in one way or another. Superfans will be particularly delighted to see Denis Lawson's Wedge Antilles still piloting a fighter; by my count the only rebel pilot to survive since the days of the original Death Star.

There are visually arresting new locations to add to the trip down memory lane, including a Burning Man festival with aliens, the ruined Death Star lashed by vicious seas and a magnificently creepy Sith home world. Richard E. Grant joins the cast as a suitably dastardly inheritor of Peter Cushing's malevolence. The acting, particularly Daisy Ridley and Adam Driver's is-this-hate-or-love tension, is perhaps the best we've seen across the nine films, and the one-liners scattered throughout for comic relief are a joy.

We sat through all of the credits, listening to John Williams' now-classic music, wishing it weren't really over. I could have sat through the whole thing again. Immediately. Pretty much the way I felt on that hot, sticky night in 1977. I probably won't see The Rise of Skywalker another 10 times in the cinema, but there's no doubt I'll be buying it on release and watching it again many times in the future. There are times you just need to give in to your inner 12-year-old.