Maybe it’s the drama of his time here, his first visit on the run from a murder charge and his second to die after a horrifically violent revenge attack. He was a broken genius who didn’t even make it to 40. Perhaps it’s the fact that, unlike the multitude of famous artists associated with Rome and Milan, he stands well above everyone else who worked in Naples. It could be that his focus on humble realism and the interplay of the grim and the glorious perfectly matches the feel of this city. Or maybe it’s that he left three of his best here: the most enigmatic, the most powerful and the most poignant. Whatever the reason, many tourists to Naples hit the Caravaggio trail to drink in those three works, and we were ready for the pilgrimage.

It wasn’t, however, as easy as you’d think. Under normal circumstances, the paintings live in three different buildings scattered across Naples; do-able in a day though you may not be able to fully appreciate all the rest of the art they share space with. We discovered, however, that one of the three was out of the city on loan.

Fortunately, St. Ursula was enjoying superstar status at the National Gallery in London, so we could visit it when we got home. The Seven Works of Mercy was hanging in the church of Pio Monte della Misericordia, where it had been since being painted for the charitable foundation in 1607. But where was The Flagellation of Christ? It had been on loan to the Donna Regina museum, but posters throughout the city clearly stated the special exhibition ended on 28 February. The web site of the Capodimonte Museum clearly stated that the loan ended at the end of March. It was mid-April. So we piled in a taxi and headed out of the town centre to the museum housed in the old royal palace, only to discover that not only was the Caravaggio still on loan … but it was about 100 metres away from where we’d gotten our taxi in the first place. We also learned Capodimonte’s most palatial rooms are not open on Sundays. Another somewhat important detail not mentioned on the museum’s web site.

Sightseeing in Italy always requires a hefty dose of flexibility.

Even without its star sights, the Capodimonte museum was a useful starting point for an exploration of Caravaggio. Most of the second floor, which is comprised of traditional galleries rather than palace interiors, hosts an exhibition on Naples in the time of Caravaggio. This explores the financial and artistic boom taking place in the city in the 17th century. It lays out the politics and explains how the Bourbon monarchs invested in the arts to display their power and bring tourists to their city. They went beyond painting and architecture to support a china factory at Capodimonte, wood carving, and the nativity scene figures that are so popular today. Then you get to wander through room after room of artists who were influenced by, and in many cases competed with, Caravaggio. There are some striking works here but, on the whole, the exhibition sets you up to better appreciate just how extraordinary an artist he was compared to everyone else. Only a large canvas by Artemisia Gentileschi stands out as comparable; it’s the blockbuster you don’t want to leave without seeing.

Moving on to the actual Caravaggios, it makes sense to see them in the order they were painted. That means starting with the enigmatic one: The Seven Works of Mercy. The story usually told is that Caravaggio was commissioned to do seven paintings to hang above each of the seven chapel altars in the round church of Pio Monte della Misericordia, and that the often-rebellious artist chose to pack all seven into one blockbuster scene. Caravaggio biographer Andrew Graham-Dixon reveals the truth: his brief from the beginning was to pack the scene. It wasn’t even for the current church. The finished work was so impressive, and so instantly famous, that the charitable foundation that commissioned it built a new church … the one you see today … to better glorify it.

The Seven Works does indeed hang in a beautiful building, with lavish inlaid marble details, paintings above the other altars and sculptural works in niches, but it’s hard to pay attention to anything besides Caravaggio’s blockbuster. Like a magnet exerting its forceful pull, the painting captures all eyes from the minute people cross the threshold, and there’s a perpetual gaggle of humanity gathered beneath it, staring up in slack-jawed awe.

Part of its attraction is the intellectual puzzle it presents in trying to identify the seven acts. Even if you know what you’re looking for, it takes a while to figure out what is essentially a Neapolitan street scene circa 1607. The lady offering her breast to the old man behind the prison gate is rather obviously visiting the imprisoned and feeding the hungry. People who know Catholic saints will probably pick up St. Martin cutting his cloak in half to clothe the naked at the bottom right. But most will need to turn to a guide for the rest. Burying the dead, for example, is represented by the dirty feet of a corpse being carried away into the darkness.

Fortunately there’s a 3D model you can get your hands on that explains each. It’s intended for the vision impaired but is useful for everyone. This is the kind of painting you can stare at for ages, moving from one perspective to another, trying to figure out what’s going on and what all those hyper-realistic people are thinking. My favourite part is the vortex of whirling angels coming in from the top to throw light on the scene and bring down Mary and the infant Jesus as witnesses. It’s mad, and wonderful.

While the Caravaggio dominates, you really should tear yourself away long enough to appreciate a series of sculptures in carved coral that deliver a modern take on the Mercies. Artist Jan Fabre uses small pieces of coral carved into the familiar shapes of Neapolitan jewellery … horns, flowers, beads, spheres … to assemble much larger works that speak to the topics. They’re in niches around the side altars and they are magnificent.

On to the powerful one. Sightseeing in Italy always requires a hefty dose of flexibility.

Even without its star sights, the Capodimonte museum was a useful starting point for an exploration of Caravaggio. Most of the second floor, which is comprised of traditional galleries rather than palace interiors, hosts an exhibition on Naples in the time of Caravaggio. This explores the financial and artistic boom taking place in the city in the 17th century. It lays out the politics and explains how the Bourbon monarchs invested in the arts to display their power and bring tourists to their city. They went beyond painting and architecture to support a china factory at Capodimonte, wood carving, and the nativity scene figures that are so popular today. Then you get to wander through room after room of artists who were influenced by, and in many cases competed with, Caravaggio. There are some striking works here but, on the whole, the exhibition sets you up to better appreciate just how extraordinary an artist he was compared to everyone else. Only a large canvas by Artemisia Gentileschi stands out as comparable; it’s the blockbuster you don’t want to leave without seeing.

Moving on to the actual Caravaggios, it makes sense to see them in the order they were painted. That means starting with the enigmatic one: The Seven Works of Mercy. The story usually told is that Caravaggio was commissioned to do seven paintings to hang above each of the seven chapel altars in the round church of Pio Monte della Misericordia, and that the often-rebellious artist chose to pack all seven into one blockbuster scene. Caravaggio biographer Andrew Graham-Dixon reveals the truth: his brief from the beginning was to pack the scene. It wasn’t even for the current church. The finished work was so impressive, and so instantly famous, that the charitable foundation that commissioned it built a new church … the one you see today … to better glorify it.

The Seven Works does indeed hang in a beautiful building, with lavish inlaid marble details, paintings above the other altars and sculptural works in niches, but it’s hard to pay attention to anything besides Caravaggio’s blockbuster. Like a magnet exerting its forceful pull, the painting captures all eyes from the minute people cross the threshold, and there’s a perpetual gaggle of humanity gathered beneath it, staring up in slack-jawed awe.

Part of its attraction is the intellectual puzzle it presents in trying to identify the seven acts. Even if you know what you’re looking for, it takes a while to figure out what is essentially a Neapolitan street scene circa 1607. The lady offering her breast to the old man behind the prison gate is rather obviously visiting the imprisoned and feeding the hungry. People who know Catholic saints will probably pick up St. Martin cutting his cloak in half to clothe the naked at the bottom right. But most will need to turn to a guide for the rest. Burying the dead, for example, is represented by the dirty feet of a corpse being carried away into the darkness.

Fortunately there’s a 3D model you can get your hands on that explains each. It’s intended for the vision impaired but is useful for everyone. This is the kind of painting you can stare at for ages, moving from one perspective to another, trying to figure out what’s going on and what all those hyper-realistic people are thinking. My favourite part is the vortex of whirling angels coming in from the top to throw light on the scene and bring down Mary and the infant Jesus as witnesses. It’s mad, and wonderful.

While the Caravaggio dominates, you really should tear yourself away long enough to appreciate a series of sculptures in carved coral that deliver a modern take on the Mercies. Artist Jan Fabre uses small pieces of coral carved into the familiar shapes of Neapolitan jewellery … horns, flowers, beads, spheres … to assemble much larger works that speak to the topics. They’re in niches around the side altars and they are magnificent.

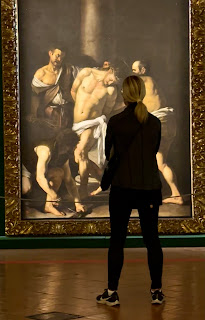

The Flagellation of Christ is one of the most emotionally arresting pieces of art ever created. Caravaggio takes us close in to the life-sized action as an exhausted Christ is lashed to a column in anticipation of his torture. He’s surrounded by soldiers who treat this as part of their job, perfunctory and emotionless. The man in the bottom corner is tying together the branches he’ll soon use to scourge Christ’s flesh. You don’t need to be a Christian to appreciate this painting. It’s an eloquent and horrifying essay on man’s inhumanity to man. If you believe, it is … as Caravaggio intended … like being present and a witness to one of the most important moments in human existence.

I can’t remember a painting ever making me cry before. But weep I did. I’d seen this one in reproduction many times but the impact of the real thing packs an enormous punch.

That’s magnified by the exceptional temporary display. The Diocesan Museum of Naples sprawls over a complex of two churches, both called Donnaregina (old and new) and their accompanying monastery buildings. The new church is a classic explosion of Baroque excess, with multicoloured marbles, whirling saints, dramatic paintings and lashings of gold everywhere. Unusually, there’s a choir loft not just above the entry, but above the altar, and that’s where The Flagellation currently hangs. It is alone in the large, dark space, illuminated by a spotlight just as Caravaggio lit his subjects. The curators have placed a line of remarkably comfortable black leather sofas along the edge of the loft, back to the church below and face to the painting. You’re invited to linger. Sink in. Contemplate.

A museum employee told me that the painting would go on loan to one or two other places in Italy before being returned to the Capodimonte Museum once its current renovation is complete. There is, naturally, no information I can find on the internet to confirm this. Seeing this painting in the next couple of years will require detective work.

I probably wouldn’t put the Donnaregina complex on my top 10 list for Naples without the Caravaggio, but if you’re here do take the time to go over to the old church, which has a choir loft that runs two thirds of the way across the length of the building and features a spectacular series of late medieval frescoes under an exuberant carved wooden ceiling.

I probably wouldn’t put the Donnaregina complex on my top 10 list for Naples without the Caravaggio, but if you’re here do take the time to go over to the old church, which has a choir loft that runs two thirds of the way across the length of the building and features a spectacular series of late medieval frescoes under an exuberant carved wooden ceiling.

With Caravaggio on the brain I couldn’t help but get to the National Gallery soon after my return from Naples to complete the trifecta. The loan of St. Ursula celebrates the museum’s 200th anniversary this year, and the crowds waiting to see the painting underline Caravaggio’s appeal to modern audiences around the world. (Although I was interested to note that on my visit at least a third of the people around me were speaking Italian.)

Like the rest of the main museum, seeing this painting is free, but it’s displayed in its own gallery just to the right (east side) of the main entrance staircase and you’ll have to queue for it, starting downstairs in the Annenberg Court. While the National Gallery’s web site encourages you to book a place to see it, the only real advantage this gives you is entry through the special exhibitions door, rather than waiting in the main building entry queue. Beyond that, nobody even checks to see your reservation when you join the Caravaggio-specific queue. On the day I visited, wait times were consistently about 20 minutes. This temporary exhibition runs until 21 July and, unlike the wandering of the Flagellation, I think you can consider that a firm date.

The Martyrdom of St. Ursula was Caravaggio’s last painting. He died two months later in horrible pain after attackers carved strips of skin off his face. Ursula lacks the sharp definition of the Works or the Flagellation. Caravaggio was desperate and on the run, a broken man who was working at speed. The detail may not be there but the emotion remains. We get St. Ursula’s moment of shocked comprehension as an arrow plunges into her heart. The soldier who fired it stands at point blank range; like the men in the Flagellation, he’s just another bloke doing his job. Onlookers behind her are horrified, but can’t do anything to stop the nightmare. Most powerful of all is the observer directly at her shoulder, howling in pain. It’s Caravaggio’s last self portrait. A genius of an artist, a problematic mess of a man, raging at the injustice of a life drawing to its premature close.

It’s poignant stuff.

If you can’t get to Naples, at least get to Trafalgar Square. And when in Naples, don’t leave without hitting the Caravaggio Trail. These paintings capture the soul of the city.

Like the rest of the main museum, seeing this painting is free, but it’s displayed in its own gallery just to the right (east side) of the main entrance staircase and you’ll have to queue for it, starting downstairs in the Annenberg Court. While the National Gallery’s web site encourages you to book a place to see it, the only real advantage this gives you is entry through the special exhibitions door, rather than waiting in the main building entry queue. Beyond that, nobody even checks to see your reservation when you join the Caravaggio-specific queue. On the day I visited, wait times were consistently about 20 minutes. This temporary exhibition runs until 21 July and, unlike the wandering of the Flagellation, I think you can consider that a firm date.

The Martyrdom of St. Ursula was Caravaggio’s last painting. He died two months later in horrible pain after attackers carved strips of skin off his face. Ursula lacks the sharp definition of the Works or the Flagellation. Caravaggio was desperate and on the run, a broken man who was working at speed. The detail may not be there but the emotion remains. We get St. Ursula’s moment of shocked comprehension as an arrow plunges into her heart. The soldier who fired it stands at point blank range; like the men in the Flagellation, he’s just another bloke doing his job. Onlookers behind her are horrified, but can’t do anything to stop the nightmare. Most powerful of all is the observer directly at her shoulder, howling in pain. It’s Caravaggio’s last self portrait. A genius of an artist, a problematic mess of a man, raging at the injustice of a life drawing to its premature close.

It’s poignant stuff.

If you can’t get to Naples, at least get to Trafalgar Square. And when in Naples, don’t leave without hitting the Caravaggio Trail. These paintings capture the soul of the city.

No comments:

Post a Comment