There are two gallery rooms upstairs set aside for rotating exhibitions. These generally draw from the rich source material of the 11,000 volume library. Shows introduce visitors to new topics and new heroines. The current exhibition, Chawton in Stitches, delivers once again … with a major exception.

This time, one of the heroines is alive.

And despite the fact that she’s just starting on her life’s journey, she’s impressed me just as much as her spiritual sisters from the library, revealing worlds to me that I knew nothing about. Emily Barnett’s world is that of needlework. Given that I can hardly re-attach a button, this is completely alien territory for me and one that I didn’t expect to find so interesting. I was astounded at both how fascinating and beautiful this small show was.

The centrepiece is Emily’s artwork The Chawton House Project, a magnificent embroidered triptych that embodies three different places around the house in a fascinating mix of materials and techniques. I went to the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition* last week, where there’s a fair amount of embroidery work, and I didn’t see anything to match the visual impact and sheer beauty of the artwork on display at Chawton.

This was Emily’s degree project to graduate from the prestigious Royal School of Needlework, inspired by years she spent working at Chawton while a student. The first panel evokes the Library Terrace with cascades of wisteria atop the embroidered names of female writers to be found inside. The centre panel gives us the rose garden, stitched with passages from the herbal of Elizabeth Blackwell. (That book also inspired the herb garden in the walled garden above the house.) The right panel brings the orchard to life, bursting with both ripe apples and apple blossom, and underpinned with snippets from the Knight family cookbook. Far more than thread, the creative work here includes linen, leather, raffia, parchment paper and gold. You’re looking at 15,000 hours of work executed over seven months, a total that will be no surprise once you see the finished product.

Displays in the room talk us through Emily’s creative process and explain, once she decided what she was doing, how she turned ideas to reality. I was astonished to learn that the roses began as stitched copies of Jane Austen’s letters, cut into petals and assembled into unique literary flowers.

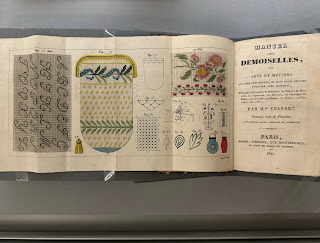

It wouldn’t be a Chawton House exhibition, however, without mining the magnificent library for more than just artistic inspiration. The first room of the show is an exploration of the history of needlework and women’s interaction with it, from the practical to the intellectual.

We get introduced to different techniques … many illustrated with helpful panels contributed by Emily … and get a look at early pattern and instruction books. We see examples of work from historic women, including an interesting sampler by a 10-year-old girl that would probably challenge most adults today. There’s also the reproduction … along with her painted portrait … of one of Mary Knowles’ extraordinary needlework portraits. She was a favourite of Queen Charlotte and well known by the Georgian court but, like so many of the women in Chawton’s library, is generally forgotten by history. (If Shonda Rhimes wants to make a stand for minority interests in Bridgerton that also has historical credibility, she should have Knowles turn up to stitch one of the family member’s portraits.)

Books from Chawton’s collection also reveal that the debate over whether needlework is demeaning or empowering has a long history. A book written by Darwin’s grandfather lays out a generally reasonable argument about character building and being productive. A rare first edition of Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Man delivers a feminist broadside, rejecting the whole practice as a way to confirm women as ornamental. Elsewhere, there’s even a nod to modern trends in feminist embroidery. I was most intrigued by passages illustrating how our ancestresses used their needlework as a barrier to hold unwanted attentions off, something any reader of Jane Austen will find familiar. Human nature doesn’t change; today we stay enraptured by our mobile phone screens to do much the same thing.

Wherever you stand on the political debate, you can’t fail to be impressed and inspired by the talent of women past and present who turned needle, thread and other materials into art. Chawton in Stitches runs until 27 August and is included in the standard admission price to tour the house. Find more information here.

Wherever you stand on the political debate, you can’t fail to be impressed and inspired by the talent of women past and present who turned needle, thread and other materials into art. Chawton in Stitches runs until 27 August and is included in the standard admission price to tour the house. Find more information here.

The Summer Exhibition was curiously flat this year. A group of us attend annually, usually assigning ourselves an imaginary amount of money to go shopping through the galleries. Traditionally, there’s a lot of shock and horror over ridiculous prices and hideously ugly or emotionally disturbing stuff you can’t imagine putting in your house. But there’s also usually a generous handful of really beautiful works you’d happily purchase if you had both a fortune and a mansion with a lot of empty walls to furnish.

This year was decidedly average, missing both the shock-horror extremes (I almost found myself wishing for reprise of a past year’s stuffed, dead cat) and the objects of deep desire. We wondered if the RA had actually issued guidance to bring the prices down, as there were far fewer ridicule-worthy price tags this year. It was actually a challenge to spend our fantasy league £50,000, though I made a big dent in my total opting for a sculpture of a dog smoking a pipe. (I told you, it was an uninspiring year.) The most desireable stuff we saw was actually priced in the £1,000 to £2,000 range and … unsurprisingly … most already featured red “sold” stickers.

Looks like the cost of living crisis is hitting rich art buyers, too.

No comments:

Post a Comment